Super-powering the newsroom: how AI could save journalism

TL;DR Journalism is in crisis. The arrival of the internet disrupted publishers’ relationship with their audience as well as their income. AI-powered technology will be a key way for them to improve the cost and quality of story detection, composition and distribution. Realigning how humans and machines work together in new ways will be the trickiest but also most important thing to get right.

This is the third in a series of long-reads about the role of ‘AI’ in various creative fields from art, design and music to journalism and comedy, aimed at the general reader. How humans and machines can work together to make creativity easier or quicker. And how society and culture play in to that.

For those who don’t know me, I started my career as a journalist working for publishers like Time Out, The Guardian and Mixmag. I spent the following 15 years of my career making digital content for brands, as head of digital at MTV, and in big creative agencies BBH and Iris. I am now pivoting my career towards AI-driven tech.

It’s so well known that it’s almost a cliché to say that journalism is under threat.

Sales of printed newspapers in the UK halved between 2007 and 2017. In the same period, newsprint advertising revenues fell by £3.2bn, a 69% decline. Other markets, such as the US, haven’t fared any better.

People increasingly get their news in places that encourage them to consume one piece of content and leave. The Guardian call these kinds of readers ‘one hit wonders’, the New York Times, ‘one and dones’. This has loosened the sense of loyalty to individual publishers or brands.

“Journalism is in a staggeringly fundamental crisis because of the internet”, David Caswell, Executive Product Manager at BBC News Labs

As a consequence of all of this, income sources that used to be central to publishing, like classified advertising and cover price have been eroded, the lion’s share of the revenue being sucked up by internet giants like Facebook, Google, Twitter etc.

According to the government’s 2019 Cairncross report, this has led to “heavy cuts in staffing: the number of full-time frontline journalists in the UK industry has dropped from an estimated 23,000 in 2007, to 17,000 today, and the numbers are still swiftly declining.”

“Journalism is in a staggeringly fundamental crisis because of the internet”, says David Caswell, Executive Product Manager at BBC News Labs, an internal innovation department within the BBC.

“It’s an invention-of-the-printing-press level issue…”, he adds, referring to the invention of the Gutenberg press which lead to the mass production of printed books and a knowledge revolution that culminated in the Renaissance. “It took 150 years for things to stabilise after that”.

Caswell’s background is an interesting and relevant blend of tech (Yahoo!), academia (Reynolds Journalism Institute), and hands-on news experience gained at the LA Times and now the BBC. He talks fast and is excited by big ideas. We will come back to him later.

So, the question is, can technology which has decimated journalism also save it?

Microsoft’s recent move to sack journalist aggregators from MSN and replace them with AI-based tools has come under fire, some of it wildly inflated to the point of moral panic,

In fact, when used properly, AI-powered technology should be able to superpower journalists, allowing them not only to do more with less, but actually do things that wouldn’t previously be possible.

The biggest issue won’t be the technology itself, but realigning processes and people around the technology. This will be a massive challenge to management who will need to win hearts and minds, and ensure that, journalists — who must be at the very heart of the process — are brought along on the journey.

THE VIEW FROM THE NEWSROOM

At the coal face of journalism there is cynicism about automation.

Dr. Stephann Makri is a Senior Lecturer at City University in London and part of the DMINR project, which aims to create tools that journalists can use to source news. DMINR, short for ‘data miner’, uses AI to research and verify stories.

He has done several sessions with journalists to establish their requirements for such a tool.

“There is cautious scepticism. There’s more and more pressure on newsrooms and on AI taking over jobs. Some are also wary that the technology will overstep the mark. They want to know the benefits — what are the meaningful connections a tool could make? How can it augment and assist journalists? ”

Michael Moran, who writes for the The Daily Star, is an industry stalwart. He has contributed to a broad range of titles, from national news publishers like The Times, The Daily Mail, The Guardian and CNN, as well as to specialist/lifestyle titles like The Jewish Chronicle, The Lady, Heat, The Face and Mixmag.

Moran has the no-nonsense, get-it-done approach of a someone who is very much in the daily news trenches. He just doesn’t have time for tools that don’t work.

“A lot of what tabloid journalists have to do is convert stories that have already been published elsewhere into stories for your publication, up to eight times a day. It’s the sort of thing which an algorithm can, in theory, do.

“Problem is when you get machine written versions of an article — they’re often not good. They don’t read like natural English. It’s like someone has taken the text through Google translate a few times.”

He sends me an example the next day and it is poor. “Brit, 29, trapped down properly for SIX DAYS with damaged leg after ‘falling in as he was chased by canine’ in Bali”, (my emphasis).

Clearly a machine has confused the noun ‘well’, meaning a shaft sunk into the ground, with the the adverb ‘well’, meaning ‘in a good or satisfactory way’ — ie ‘properly’.

And that’s just the headline — it gets worse after that.

So, let’s take a look at innovations in this space that show the way it should be done…

THE INNOVATORS I — STORY DETECTION

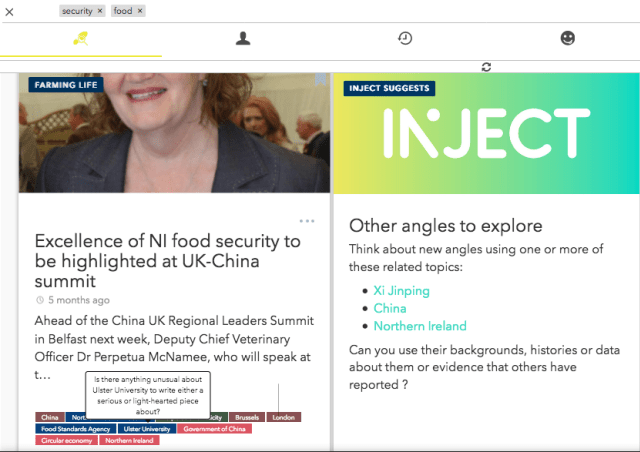

JECT.AI is a tool that has come out of City University’s Cass Business School. Its aim is to “trigger new ideas for story angles more easily and quickly”.

Essentially, where a search engine like Google gives you answers for things you don’t know — JECT aims to uncover things you didn’t even know you didn’t know. “Insights, not links,” as they put it.

I speak to Prof. Neil Maiden, the strategic lead on the project. He has a PhD in Computer Science and over 250 peer-reviewed research papers to his name. Since 2007 he has been focused on the crossover between creativity and computation. He is now Professor of Digital Creativity at the Cass Business School.

Despite his big-dog credentials, Maiden has a relaxed, soft-shoe style to match his tousled grey hair.

“Preparation is a key step in creativity,” he says, citing thinkers in the space including French mathematician, Henri Poincarré , American computer scientist, Ben Shneiderman and psychologist, James C. Kaufman.”That’s what we’re trying to augment.”

JECT.AI reads news articles 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. 400 titles every 30 mins in 6–7 languages

“We start with actual data — headlines and so on. Then we make sense of that using natural language parsing, and finally combine that with creative search. Rather than finding something similar, the system expands query in creative ways. You search for x and y, and the system gives you x and z. Stuff you didn’t know you were looking for.”

JECT.AI read news articles 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. 400 titles every 30 mins in 6–7 languages with 15–20,000 articles, indexed and tagged

It has just started a commercial life outside of the realms of academia, and is due for formal launch in the Autumn of 2020.

THE INNOVATORS II — STORY COMPOSITION

Where JECT.AI focuses on the news-sourcing side of the process, RADAR focuses on the composition of stories themselves.

Gary Rogers, is co-founder and editor-in-chief, at RADAR. He has had a career at the heart of UK news, starting off as a cub reporter at the Reading Evening Post before eventually rising to become editor of the BBC 6 o’clock news, “deciding every day which twelve stories the public needed to know about”.

Wanting to get out of the grind of the daily news cycle, he went on to spend 10 years launching TV channels and news operations in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

He’s the sort of guy you’d trust to set up anything — exuding both enthusiasm and competence.

In the first 5 months of 2020 alone, RADAR wrote 58,000 local news stories consisting of 24m words — with an editorial team of only 5 people.

His epiphany came when saw the role huge amounts of data had started to play at the heart of journalism.

“We could see there was so much data becoming publicly available from the police, the NHS, Public Health England and so on. It was just sitting there and never touched. It’s very hard for an individual journalist to justify spending two hours understanding one spreadsheet for one story.”

“I started writing stories by hand, just for London, based on local data. We realised very quickly that instead of one story about crime figures, you could easily do it at a borough-by-borough level, and get 33 stories out of it”

Just like Michael Moran, he knows that news stories are structured in a relatively formulaic way. “Where the Merton story might be about burglary, in Hackney it might be about, say, street crime. You could just ‘nose’ the story accordingly, ” Rogers says, referring to the pyramidal structure of news stories, with the most relevant/important facts, the ’nose’, at the start.

“I thought, there must be a technological solution to this”.

The solution was what they call Natural Language Generation or NLG.

WHAT IS NATURAL LANGUAGE GENERATION (NLG)?

NLG is a technique which allows computers to write text that reads like ‘natural’, human copy.

It’s part of the wider field of natural language processing (NLP) that has undergone a transformation in the past 5 years or so, driven by the realisation that much of human language is predictable if you use the right statistical techniques.

One famous model is GPT-2, was released by the OpenAI foundation last year. Word by word, it hazards a guess at which word should come next, based on 8 million documents it has seen previously.

A good way to get a feel for it is to try the Talk To Transformer website which is based on based on GPT-2. It generates a few sentences based on text you give it to start with. Give it some Dickens, it will write like a Victorian, give it Catcher In The Rye and it will give you American self-loathing.

Like a lot of technology, it can be used for good or not so good. David Caswell refers to it as an ‘automated bullshitter’. What it generates sounds like natural language, written by a human, but since the computer doesn’t have any actual knowledge of the world, it’s actually more like a stream of consciousness — or a fever dream of randomness, depending how you look at it.

The successor to GPT-2 is more sophisticated. (You don’t need to use machine learning to guess that the follow-up to GPT-2 is called ‘GPT-3’). It works not only word-by-word, but takes into account the whole document. This gives it the ability to reference things it has already mentioned — ‘callbacks’. This makes its output seem all the more human.

The worry is that this kind “high-quality auto-generated bullshit” will come to dominate the media environment, potentially drowning out real news with fake news, just as bad money drives out good.

But this differs hugely from the kind of NLG used by people like RADAR, which is more structured. RADAR take the key facts, selected at a high level by a journalist, and lets NLG convert them into readable stories.

Because the facts of the story have been created separately from how that story is presented, it allows the machine to output it in numerous different ways — different lengths, different languages or just in different styles.

“It’s ‘meta journalism’, focused at the level of the pattern and the policy rather than at the level of the specific instance or the article,” says Caswell,

“It’s is way more complex than the ‘slot-filling’ of mail-merge. It’s logic trees that are 15 layers deep. The innovation, around 2013, was creating an interface that allows humans to manage that level of complexity”.

You can see how a structured story like this is built from the ground up by David Caswell in this video.

So, based on NLG technology of the ‘good’ variety, RADAR was set up by Gary Rogers and his business partner, Alan Renwick. They subsequently went into partnership with one of the biggest providers of news in the UK, the Press Association.

They now distribute stories to 400 news organisations. In the first 5 months of 2020 alone, RADAR wrote 58,000 local news stories consisting of 24m words — that’s with an editorial team of only 5 people.

Crucially, at RADAR, journalists are an essential part of the mix.

“RADAR stands for Reporters And Data And Robots. We deliberately put the reporter first, not the robot”, says Gary Rogers.

“A machine can’t find stories — journalists find stories, particularly where there is limited data.

“Sometimes the most important part of a story may not even be in the data. And even if it is, you may need context via an expert, comments, responses or opinions on the story which only a human can do. But, machines do allow humans to do more, to scale up. People are better at writing stories, machines are better at mass manufacturing.

“Written by a human, produced by a robot is how we sometimes refer to it.”

“A machine can’t find stories — journalists find stories, particularly where there is limited data.” Gary Rogers, RADAR

THE INNOVATORS III — STORY DISTRIBUTION

You know the social media phenomenon that is TikTok. Zero to 800 million users in five short years.

But what you may not know is news aggregation app Toutiao, owned by TikTok’s Chinese parent company, Bytedance.

Toutiao means “headline” in Chinese and is known as TopBuzz in the west. Its AI-driven algorithm generates a tailored news feed for each user by analysing both the content itself, data from its users and how users interact with the content. The stories and videos come from over 1.1 million publishers — traditional news publishers, government institutions and companies.

(There is a very detailed analysis of how their algorithm works here. Although it’s in Chinese, it is easily translatable using online tools.)

With 115million daily active users, it is big, but more interesting is how engaging users find it. Although usage is primarily through an app, which makes it hard to get data, you can see from the web version just how key engagement metrics are all multiples better than its western rivals.

There is a massive fight to be the ‘presentation layer’ for news, the main news aggregator and therefore owner of the consumer relationship, with news providers themselves relegated to a background role.

Alongside existing players like Google News and Apple News, there are new entrants like News Break (Particle Media, also Chinese), Knewz (Murdoch’s News Corp.), SmartNews (founded in Japan), DailyHunt (India’s Verse Innovation).

The future of news won’t just be the stories themselves, but also how they are presented.

Ironically, while News Corp’s Knewz boasts of not being algorithmically curated, it has fallen into exactly the trap that machines are often accused of, creating a biased feed.

According to the Columbia Journalism Review, “despite touting the ‘range of views and perspectives in the stories it showcases,’ one in every eight stories came from three conservative sources: the New York Post, Fox News, or the Daily Mail… The top one percent of outlets received more promotion than the bottom 63 percent.”

Proving yet again, that human decision-making will remain critical.

Nevertheless, what all these new applications show is that the future of news won’t just be the stories themselves, but also how they are presented.

The BBC’s David Caswell points out that this is already happening. “We published the results of the 2019 general election at a constituency level — a different story for every constituency and in two languages, English and Welsh.

“In future we will also be able to personalise by style. Put it into Radio 4 language or Five Live language, long versions, short versions, depending on the user.”

THE BARRIERS TO BUILDING THE NEWSROOM OF THE FUTURE

As we’ve seen, AI has the power to make journalism better:

- As tool to enhance productivity and reduce costs, make publishing more competitive — particularly at a local level

- Get to news stories that never would have been gotten to, hidden in public data sets, or other spaces that can only be detected by the unparalleled power of machine-powered pattern-spotting

- Deliver really personalised news — not just the interesting stories, but in the tone of voice and at the length the user wants

- Ability to quickly examine the kinds of big whistle-blower data drops that are increasingly common. (Last year’s Russian leak was 175 gigabytes — and the its full impact may not be felt for some time.)

- Better questioning government, holding them to account. This is particularly true at a local level

So, what is standing in the way of big publishers adapting their operations to take advantage of these innovations?

Established industries nearly always struggled to change. Take the record industry which has had a 20-year journey back to income growth. The same will be true of publishing, possibly more so, with quite a few things standing in the way of systemic change.

New processes, new skills

“Journalism is one of the few human activities which hasn’t been industrialised. When you move from hand-crafted to industrial, you have to move up a level of abstraction, you’re writing at higher level, at the level of the pattern,” says the BBC’s David Caswell

RADAR’s Gary Rogers talks a lot about the human side of his business. How he hires their journalists, how they get trained, the process and workflow. More than he talks about the tech.

“I tried out lots of different systems before I arrived at the one we use. My key test was, ‘could a journalist use it?’ It’s easier to teach data skills to a journalist who can already write good copy, than teach a coder how to be a journalist”, he says.

“Even then, it can take a writer up to three months to get their head round it. It really plays with your mind at the start, but eventually you can envisage it. It’s like a 3D structure.”

This has major implications for how existing workflows and processes would be impacted, as well as the retraining that will need to happen.

The machines aren’t taking over, but journalists, who typically come from arts backgrounds, often don’t have the expertise needed to get to grips with the technology. Tech that is going to be their toolset in the future.

Audience expectation

Then there is the question about how it will be perceived by the audience to know that the news they are paying for has been written by a computer.

Dan Gilbert, Director of Data at News UK, the publisher of The Times and The Sun, says, “we are a paid proposition and believe that the people who pay to read us will expect what we produce to be reported by humans.”

News UK so far limit their application of AI to helping sub-editors and getting their stories distributed in the right places.

“It is difficult to predict where machine learning developments will take us in the next few years, however we believe that human authorship and curation will continue to be critical in a world where there is increasing uncertainty over the provenance and reliability of content.”

How can publishers overcome this need for human-told stories? Is it as big an issue in the minds of consumers as it is in the minds of publishers?

Power struggles

There are also vested interests at play.

“There is a lot of power in editors’ hands,” says David Caswell. “Choosing the angle of the story and who to interview, what quotes to choose. If you had an auto curation and story-finding tool, the algorithm would take that power away.”

Neil Maiden from City University noticed a lot of pushback journalists themselves. “We had a meeting with the NUJ after China’s Xinhua state news agency revealed a news-reading avatar. There was aggressive resistance, particularly from freelancers. There is a perception that automation kills creativity.”

How can the industry embrace technology without seriously affecting the quality and number of jobs in the business?

All of this is leading to institutional inertia.

According to RADAR’s Gary Rogers, “all of this [work] is disruptive to established businesses and easier for startups. That’s why a lot is only happening at the edges, in one-off projects, but not affecting the fundamentals of how the news industry work.”

That the major publishers are not taking up AI-powered tech up at a greater pace is a shame. The technology could be such a massive game-changer for an industry much in need of one.

If you like this article, please let other people know by ‘clapping’ for it using the button below or to the left.